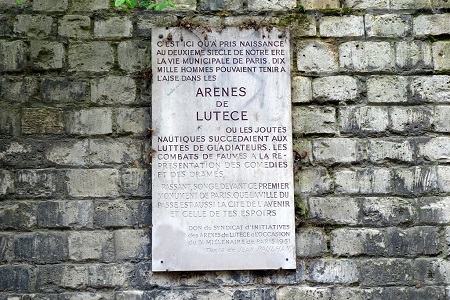

The Hidden Secrets of the Arenas of Lutetia

This monument is the oldest one in Paris (if we don’t count the Luxor Obelisk at Place de la Concorde, which was imported from Egypt).

Its remains date back to the 1st century, during the Roman Empire.

This monument is unique in that it was both an arena (gladiator and wild beast combats) and a theater (mimes, shows, musicians).

Located in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, it is not far from the metro station on line 2: Place Monge.

How actors managed to make themselves heard in the arenas of Lutetia

The capacity of this arena was estimated at around 12,000 seats.

That meant the actors had to speak quite loudly in order to be heard.

To achieve this, they spoke through raised niches that allowed the sound to project all around the arena.

An effective way to avoid sore throats for the actors.

These niches are still present today, and you can see them when sitting near the benches.

The stage of the arenas of Lutetia

Another wonder of the Lutetia arena is its stage.

Still visible today, it benefited from beautiful natural lighting when the sun set in the west (the plays were mainly performed in the afternoons).

Why are there cages in the arenas of Lutetia?

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, this stage also served as a battle arena.

Various types of events were organized in the battle arena: gladiator fights, executions, or wild beast combats (photo above).

These wild beasts were kept in these cages before their entrance onto the stage.

They were wild animals imported from Africa such as cheetahs or lions.

But these cages also allowed gladiators to gather themselves just before a fight (like locker rooms).

Today, these cages are still visible and are now used to store chairs.

Did you know this monument almost got destroyed?

Despite everything, this arena truly faced some terrifying threats.

Around the 19th century (1883), the authorities nearly destroyed the arena to turn it into a depot for horse-drawn omnibuses (in preparation for building a station for the Omnibus Company).

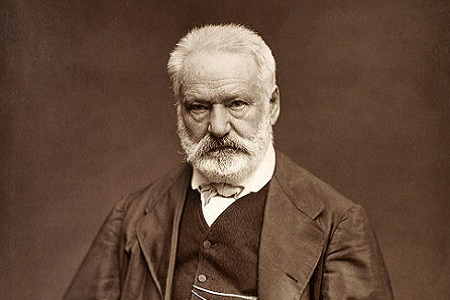

But the worst was fortunately avoided thanks to one man in particular: Victor Hugo.

He addressed the President directly, saying:

«Mr. President, it is not possible that Paris, the city of the future, should renounce the living proof that it was once the city of the past. The past leads to the future. The arenas are the ancient mark of the great city. They are a unique moment in history. The municipal council that destroys them would, in a sense, be destroying itself. Preserve the arenas of Lutetia. Preserve them at all costs. You will be doing a useful act, and even better, you will be setting a great example.»

He, along with other contemporaries of the time, fought for the preservation of these unique remains in history.

Thanks to their actions, the arena avoided a terrible fate and was gradually restored.

The largest arena in Gaul

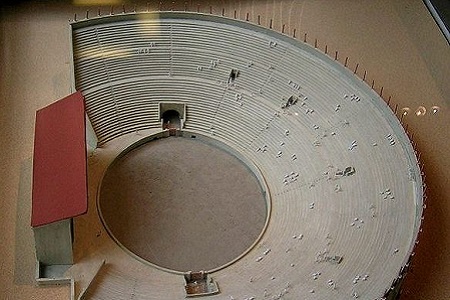

In 1918, architect Jean-Camille Formigé carried out an in-depth study of the monument for the Commission of Old Paris.

Facing a deteriorated structure, he based his work on research of other Roman amphitheaters such as the Colosseum in Rome and the arena of Nîmes.

He then discovered that the preserved remains indicated that the arena was 135 meters long with seating at a 35° angle.

That’s when he realized this arena was the largest in Gaul.

Behind the amphitheater, the architect also imagined the presence of a hippodrome for chariot races. However, no traces were ever found.

Today, the space delights soccer and pétanque enthusiasts who gather here for a bit of relaxation.

The stands

These stands formed what was then called the “Cavea.”

They could accommodate between 12,000 and 17,000 people (which means the arenas of Lutetia mainly attracted the inhabitants of Lutetia itself).

Over time, numerous initials were discovered engraved on the stands, representing the names of the owners of reserved seats.