The Secrets of the Panthéon in Paris

Jewel of the French capital, this historic monument has left its mark on the history of France.

Founded in the mid-18th century (1744), the building was commissioned by Louis XV, who had fallen seriously ill with a high fever during a military trip to Metz with his mistress, Mme de Châteauroux.

Construction began in 1750 and was finally completed in 1790.

Located in the French capital, in the Latin Quarter, it has witnessed many major events in the history of France over time.

We are going to share with you 10 anecdotes you probably didn’t know about this French historic monument.

To discover the Panthéon in a different way, let yourself be tempted by our incredible treasure hunt in the Latin Quarter.

What is the origin of the Panthéon in Paris?

The idea for its creation came from King Louis XV himself.

During the period when he was gravely ill, he turned to his faith and prayed to Saint Genevieve (patron saint of Paris) to miraculously save him.

He also promised to build a magnificent basilica in her honor if she cured him.

He recovered and decided to keep his promise by founding this church (now the Panthéon), even laying the first stone himself in 1764.

How was the Panthéon financed?

This monumental project was financed by public lotteries, which raised nearly 400,000 livres for its construction.

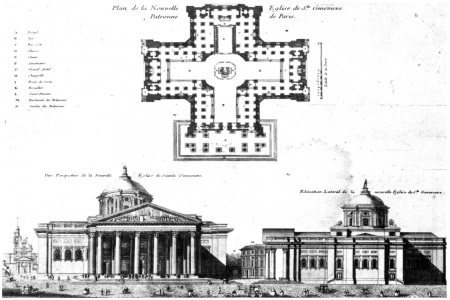

The architecture of the Panthéon in Paris

To pay tribute to Saint Genevieve for miraculously saving him, Louis XV turned to a great architect: Jacques Germain Soufflot.

His ambitious project was for the Panthéon to rival two other world-renowned religious institutions: St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

He drew inspiration from the façade of the Roman Pantheon of Agrippa for the Parisian Panthéon.

This project was conceived by the King in 1744 and finally completed in 1790.

The changing role of the Panthéon in Paris

As we have already mentioned several times in this article, the building was originally meant to be a church.

But with the French Revolution in 1789, the people began to see it as a Panthéon.

A place where only the heroes of the French nation could rest after their deaths, except for military heroes (who already had their own Panthéon at Les Invalides).

Some of the greatest names now rest in peace in this sanctuary: Voltaire, Rousseau, Émile Zola, Jean Jaurès, Monet, Pierre and Marie Curie, Jean Moulin, Pierre Brossolette… So many French figures who left their mark on the history of the country.

In fact, the Panthéon is the only place where you can see Rousseau and Voltaire facing each other (despite their very different beliefs).

By contrast, Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas, who were close friends, rest side by side, even after their deaths.

A fragile architecture

At first, the French were very impressed by the structure of this building, but they remained skeptical about its solidity.

Stones began to crumble, and there were fears of the dome collapsing.

At the end of the 18th century, many experts and architects studied it under the Directoire, which lacked the funds to consolidate the monument.

It wasn’t until Napoleon came to power that significant renovation work was finally carried out, especially on the pillars of the dome.

Those ejected from the Panthéon

To this day, being ejected from the Panthéon is very rare, but possible if, and only if, one has committed a very serious act.

This is what unfortunately happened to two French figures: Honoré-Gabriel Riquetti de Mirabeau and Jean-Paul Marat.

The first had been buried inside the Panthéon as a hero of the people (he had become a deputy for the Third Estate, despite belonging to the Nobility).

But when secret documents revealed his covert ties with the monarchy, his remains were removed from the Panthéon.

He was replaced that same day by the famous journalist, doctor, physicist, and politician Jean-Paul Marat.

A poor choice, as Marat also lost his place at the Panthéon because of a decree stating that no one could be interred in a public place or Assembly unless they had been dead for at least 10 years. Since then, neither of their remains have ever been found…

A place of scientific experiments

The Panthéon also played an important role in science in the 19th century thanks to physicist Léon Foucault.

At that time, he was searching for a large structure capable of hosting his pendulum (which proved that the Earth rotates).

The first public demonstration took place in 1851, and it still works perfectly to this day.

Another scientist also used the Panthéon for his experiments: Eugène Ducretet.

In 1898, he succeeded in creating a French radio link between the Panthéon and one of the most visited monuments in the world: the Eiffel Tower.

This allowed sounds to be transmitted from the Panthéon to the Eiffel Tower.

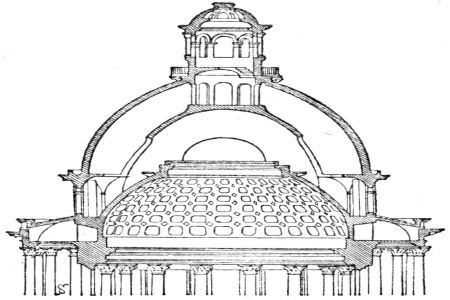

The secret of the Panthéon’s dome

This mysterious dome holds great surprises.

This historic monument, located on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, is visible from many places across Paris.

The secret lies in the fact that it is made up of three nested domes:

– Inner dome: allowing light to pass through

– Intermediate dome: decorated with sumptuous paintings and visible through the opening

– Outer dome: visible from the outside, built of stone and covered with lead

Mitterrand’s roses

In May 1981, the President of the Republic (François Mitterrand) came to honor the national memory of the Panthéon with a rose, in front of the cameras.

Once inside the secular temple, he placed three roses on the tombs of Jean Moulin, Victor Schœlcher, and Jean Jaurès, always holding one in his hand.

The public saw this as a “floral miracle,” but in reality, technicians discreetly handed him roses behind pillars before each shot.

A guard also stayed close to him to prevent him from getting lost inside the Panthéon (although this unfortunately happened anyway).

Women in the Panthéon

Despite everything, women remain very underrepresented in the Panthéon, with only five admitted so far.

Sophie Berthelot (1837-1907)

Scientist, admitted in 1907 as the wife of Marcelin Berthelot.

Marie Curie (1867-1964)

Polish-born physicist and chemist, naturalized French. She was admitted in 1997 alongside her late husband Pierre Curie. Interestingly, her lover, Paul Langevin (a former student of Pierre), is also present in the Panthéon, not far away. At the time, their relationship, which began after Pierre’s death, caused a scandal because Langevin was young and already married. People branded Marie Curie as a “homewrecker.”

Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz (1920-2002)

Niece of General de Gaulle, a great resistance fighter against poverty. She was admitted in 2015.

Germaine Tillion (1907-2008)

Renowned ethnologist and resistance fighter. She was also admitted in 2015.

Simone Veil (1927-2017)

She fought for freedom and survival during the Second World War (1939-1945). She was admitted in 2018 alongside her late husband Antoine Veil. She also played a crucial role in advocating for women’s presence in this secular temple, notably in a 1992 interview with *Le Point*.

Conclusion

The Panthéon is not just a monument; it is a true open book on the history of France. From its construction under Louis XV, to its transformation into a republican temple, through its architectural secrets and the great figures it shelters, it embodies the nation’s memory.

👉 And if you want to discover it differently, dive into our treasure hunt in the heart of the Latin Quarter: a fun and unusual adventure that will let you explore the Panthéon from a unique angle, while having fun.